I see in your future...cars, with a chance of more cars

A reminder to not be intimidated by the unsophisticated methods of traffic engineering & transportation planning.

A journalist interviewing me about my career arc wanted to understand how my background informs my outlook for the future. It’s a better question than the softball “why were you drawn to this career” that bores us all to death in professional journals and podcast interviews.

My hopes for the future. I told him one way to sum it up would be senior citizens riding bikes at night, in dark clothing, without helmets. That’s my fantasy of a typical evening in Anywhere, USA.

His response to that was a fatalist type of “I get it, but that’s not possible because of traffic engineering.” He wanted a bicycle-friendly future, but read too many stories about how that’s incompatible with the way planning and public works departments analyze travel demand and mobility.

His tone got me on the edge of my seat because did I have some good news for him. The perceived foe, this insurmountable team of highly educated and credentialed professionals would never let lowly old bicycle urbanism take hold. But what I knew to be true is that the outcomes predicted by experts are based on the misuse of analysis tools.

I never studied city planning or anthropology or cartography in high school or college. I didn’t have an academic perspective on human-scale design in the late 90s and burst into the workforce on a mission to make streets safe and happy places for people.

My goal out of college was to have a job that I could tolerate doing for the rest of my life. Don’t let my civil engineering degree fool you. The type of math I excelled at was calculating the number of trips I could make around the office for small-talk and still knock out the work my boss assigned.

My career started as a traffic engineer. It’s easy to mock that profession (and I do plenty of it), but I enjoyed the work. Traffic made sense to me in ways that stormwater, steel structures, or soil mechanics never did. The evolution of my personal quest for human-scale design (good urbanism!) can probably be summed up with one simple story.

I’m sitting in my cubicle doing what traffic engineers do—setting a fantasy football lineup. After my lineup was set, I was using a computer model to analyze rush hour traffic for a big corridor study. This particular project happened to be on a street right around the corner from the office, so I knew it well. (Route 50 near I-66, for you NOVA insiders.)

They didn’t teach us transportation models in college, so I had lots of questions. I was brave enough to speak up because I want to do my work correctly, but too embarrassed to ask follow-up clarifying questions.

I was going through the default settings of the model: lane width, number of lanes, number of seconds the light stays green, percentage of truck traffic, and so on. One of the input sections has a place where you can create a ped-phase.

“What’s a ped phase?”

“That’s where only pedestrians have a green light, and cars in all directions wait.”

“Oh. Should I put one in?”

“No, we don’t do that in Virginia.”

“Ok. What about this box that converts the intersection to a roundabout?”

[snickers] “Let me know if you have any more questions.”

My boss just figured I was joking, so I mirrored his smirk and walked back to my cubicle. Later I asked another employee who was older than me (i.e. must know everything) about it and he said “Oh, we don’t do roundabouts in Virginia.”

Why not? Why’s it an option in the software? Why would other states use roundabouts if we don’t? I must’ve sounded like a toddler. And it wasn’t just about roundabouts or pedestrian phases, it was all the things:

Design speed,

lane width,

lane additions to reduce delay,

reasons for level of service analysis,

volume-per-lane analysis, and

the length of a yellow phase before red.

The answers were generally the same: We do it this way because this is the way it’s been done.

Modern society is under the impression that infrastructure projects are the result of objective science. That's wrong.

Imagine my surprise as a young traffic engineer when I learned street networks are planned using Magic 8 Balls that we call forecasting models. So much of 21st century mobility analysis is based on a type of astrology. Experts hand over their analysis to a public agency like the department of transportation. That agency then confiscates private property—someone's front yard or house—because a soothsayer flipped over the Magic 8 Ball and announced, “signs point to more traffic.”

I’d understand the appeal if the predictions were reliable for local planning and engineering departments, but the models are “weatherman accurate.” Meteorologists are really good at predicting macro patterns in temperatures and storm fronts, but it’s incredibly difficult to predict weather in a small zone.

That doesn’t mean weather forecasting is complete junk science. It means we the viewer are careful about how much weight we put in the news. “There’s a 40% chance of snow next Saturday” becomes “sunny and cold on Saturday” and we aren’t shocked.

Traffic engineers have analytical tools to measure the delay, speed, and volume capacity of street networks. But the reason those tools become unreliable at the project level, like a 2-mile corridor study, is that the models treat humans as 1s and 0s. They’re not set up to account for the adaptable nature of humans.

Atlanta, GA is routinely ranked as one of the most traffic-jammed cities in the country. In March 2017, one of the Interstate 85 bridges caught fire and collapsed during the evening rush hour. No one was hurt, but the interstate obviously had to close, diverting 250,000 daily vehicle trips. A quarter million vehicles, every single day, on this one part of I-85.

You can understand why fears spread that the already congested region would grind to a halt for months or even years while the interstate was closed. Instead, the 250,000 commuters and pass-through travelers just seemed to evaporate.

This was before Covid, so people traveling in and around Atlanta had to get to work, school, the store, and every other place. It turns out that humans adapted more like water flowing downhill, than a predetermined code. The local street network and bus system absorbed the surge in traffic while the interstate was repaired.

Real life did not comport with models. Experts swear up and down what’s possible on a street network, but they’re left in the unenviable position of “don’t believe your lying eyes.”

Carmageddon predictions are made all the time at various levels of intensity. A waterline bursts, a football game ends, a brush fire crosses the median, or a truck overturns. Stuff happens that forces people to change travel behavior. And despite the traffic models insisting streets can’t handle new patterns, they do. People wiggle around to get where they need to be, and in some cases change the time of day for travel. This is all the more true post-Covid.

Intersection and road widening projects are a big deal, especially when astrology is used as the basis for taking private property by force. Rezoning cases and redevelopment projects are also times this comes up. Planners and engineers might bicker on social media, but they’re partners in the use and abuse of transportation predictions.

Don't be intimidated by the GIS maps and 3D models and terms like Primary Arterial or Level of Service. The basics matter, so ask dumb questions. You'll be amazed at how often the answers reveal a shocking lack of sophistication. Be prepared for “we do it this way because we’ve always done it this way,” and “the planning department makes us do it this way.”

Regardless of the response, put yourself in the conversational driver’s seat. Remember, you’re talking to an astrologist.

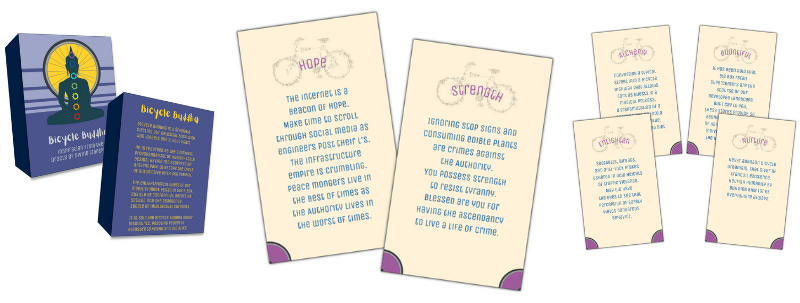

On a related note, the Bicycle Buddha Oracle Card Deck is now available in digital format, optimized for mobile phones. It’s 52 cards, perfect for that cyclist or wild-eyed urbanist in your life (especially if that person is you). It’s available in two formats:

Digital. This isn’t just a PDF you scroll through on your phone. It’s like Kindle or Audible, but for card decks. Click here to take a look.

Physical. If you’re more of a “put it in my hands!” kind of person, there are 20 boxed decks left in stock. Click here for those.

"We don't do that in Virginia"...made me chuckle. Thankfully I've never worked for the government. This still seems to be the attitude here with respect to bike lanes, traffic calming, etc. in suburban counties like Chesterfield (and sadly, Henrico, even though I know Henrico maintains its own roads). Do other counties in Virginia have much local control over their road design?