Induced demand isn't just about highway expansion projects

Incentivizing electric car culture is still incentivizing a car culture.

Last month, the New York Times ran a story about induced demand. The thing about road expansions is that they only temporarily reduce traffic congestion, but the experts only temporarily remember expansions don’t work. Ok, they don’t really forget, they just don’t care to know.

Political discourse moves like a Twitter timeline—just, whoosh. I’ve written about induced demand here and here. When public works or transportation departments make driving easy and appealing, then naturally the system fills up with car traffic. It’s that simple.

Every time there's a new infrastructure bill, public agencies and government leaders clamor for federal funding to add more car lanes. They aren’t stupid. They don’t want to leave money on the table, they want to leave a legacy of delivering big infrastructure projects.

The NYT article is relevant to the current gas-to-electric push by federal agencies. If the feds are going to give handouts or subsidies, why not create incentives for car-lite living?

It's easy to praise EV adoption as an alternative to gas-powered cars. But there are three big reasons advocates risk losing credibility.

1. Battery-powered cars and gas-powered cars are both cars.

Fossil fuels have been a villain in urbanism circles for years. But as some environmental activists have said, personal electric cars are still cars. If the administration’s goal was truly to reduce car dependency, then we’d see a fundamental shift in funding programs and subsidies.

Secretary Buttigieg and social media’s Team Pete talks big about the follies of planning the American landscape around the personal automobile. I wholeheartedly agree with their statements that infrastructure is not built at a human scale, and it’s doing all sorts of damage.

"We need to stop planning everything around cars."

"But also, keep planning everything around cars."

There are over a billion cars on the road. The actions of politicians suggest reducing that number isn’t a top priority. Ok, but don’t tell us it’s a top priority.

2. Purchase price and maintenance is a big deal.

EV advocates have got to address practical concerns about high purchase prices and maintenance nightmares. If the answer is "we don't know if EVs will be cheaper, but our administration thinks it's worth it" then say that. People might disagree with subsidizing electric vehicles, but at least they'll trust the messenger to be candid.

Besides the initial sticker shock, people need to understand the ongoing maintenance issues before converting from gas to electric. Andrew Hawkins wrote a piece in The Verge about this:

JD Power surveyed 11,554 electric vehicle and plug-in hybrid vehicle owners... Despite big growth in the number of public EV chargers in the US, EV owners say the overall experience still sucks.

Maybe it’ll be worth it, I don’t have the answers or expertise. I do have questions, and so should any curious urbanist. Under all the questions is probably “without subsidy, would it make any sense for normies to replace gas cars with electric ones?”

Entrepreneur and engineer Tom Gurski has been working on this problem for several years. Here's a podcast conversation about technology he’s developed to convert everyday light vehicles like cars and SUVs to hybrid vehicles.

Hardware to Save a Planet: https://hardwaretosaveaplanet.com/e/183ly32n-tom-gurski-retrofitting-billion-cars-to-hybrid-evs

If you’re curious about the cost/benefit comparisons of full fleet conversation vs. hybrids, you’ll appreciate Tom’s research. Connect with him on LinkedIn and tell him I sent you.

3. The biggest selling EV is getting dismissed as if it’s a toy.

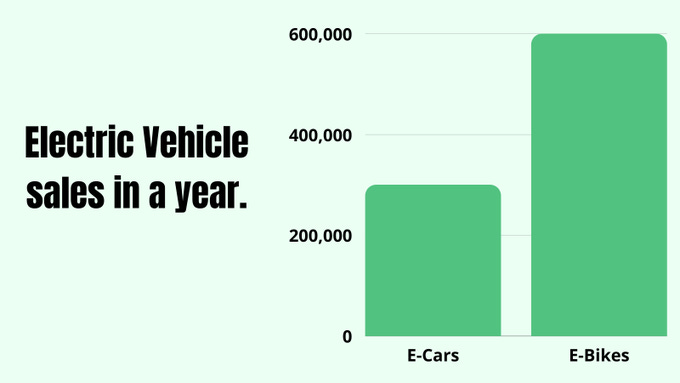

Bicycling can be recreation, but bicycling is the most basic form of transportation after walking. What a happy coincidence that the best selling electric vehicle is a bicycle. Read about it here and here.

If leaders looking for some political points were to build a charging network that reflects real world conditions, they’d be all-in on e-bike infrastructure.

If you’re going to criticize induced demand in transportation planning, then be consistent. Incentivizing electric car culture is still incentivizing a car culture.