Live the automotive dream

If you're upset about America's car dependency, it helps to understand the role of propaganda.

Substack only fits so much of an article into each email. Tap the title to open in your browser or in the Substack app to make sure you’re getting all the content.

This is a continuation of my last post, so be sure to read that one first.

Ads employ psychological tactics to establish emotional connections and create a sense of urgency, convincing audiences that certain products are indispensable. Cereal, shoes, detergent, computers, cars—all of it. The emotional manipulation drives consumer demand, which in turn fuels the growth of industries.

In the early 20th century, the American automobile industry experienced a remarkable surge in growth, defying the conventional economic wisdom that saturation leads to stagnation. The paradox was an enormous demand for cars despite Americans supposedly having "enough."

How to win fans and influence buyers.

Propaganda wields formidable influence over public perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. We’ve come to think of it as something wicked that only evildoers dare use, but it’s as simple and common as this Merriam-Webster definition:

Pro·pa·gan·da (noun): an organized spreading of certain ideas

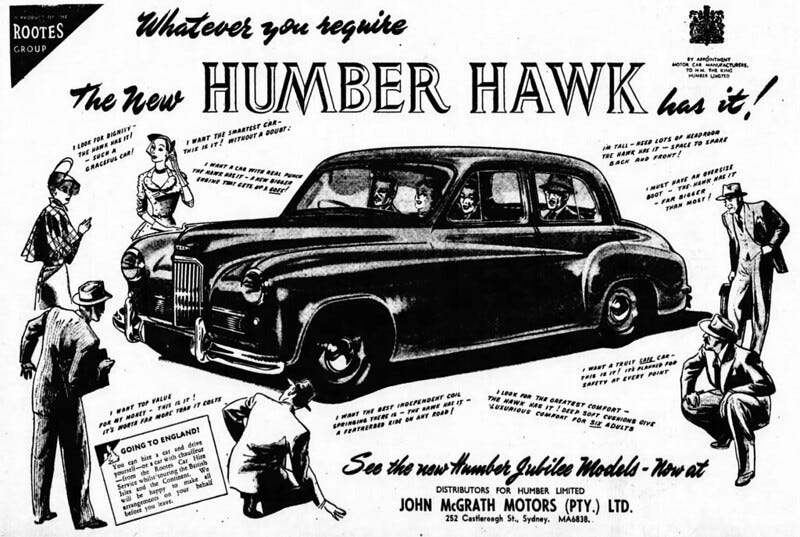

As tools of persuasion, advertisements can shape desires, create needs, and ultimately drive consumer demand. In the context of the automobile industry's growth, the power of “this could be you” messaging was reflected in annual sales figures.

The emergence of the automobile industry's giants Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler coincided with the rapid expansion of mass media. These manufacturers recognized the potential of advertising to reach millions of potential consumers and convert them into avid car buyers.

One compelling example of this is the Ford Motor Company's innovative use of assembly line production, which revolutionized the manufacturing process and led to affordable automobiles. Capitalizing on this efficiency, Ford introduced the Model T in 1908, marketed as "the car for everyman." The marketing work didn’t focus on utilitarian details, but portrayed car ownership as an essential marker of modernity and progress. “Ford: The Universal Car” was a catchy slogan that gave the have-nots a way to become one of the haves. You might not live in the same house as the elites, but you all drive the same car.

GM took a different approach by introducing a range of models that catered to diverse consumer preferences. This allowed for targeted advertising campaigns, focusing on specific demographics. For example, Chevrolet's advertising in the 1920s emphasized practicality and value, appealing to middle-class families seeking dependable transportation. Buick, on the other hand, positioned itself as a premium brand, luring wealthier buyers who wanted to stand out from the crowd. In each case, they were finding emotional hooks for their potential buyers.

In the era of television, automobile manufacturers continued to capitalize on the power of advertising. The 1950s and 1960s saw a surge in car-centric commercials that showcased features in the context of personal freedom and adventure. Iconic ad campaigns like "See the USA in Your Chevrolet" and Ford's "Total Performance" tapped into aspirational wants.

Why stop with informing when you can be persuading.

Edward Bernays is one of the most unknown but important people of the 20th century. School curriculum ought to include him when teaching about inventors and innovators.

A nephew of Sigmund Freud, Bernays was born in 1891. He came from a distinguished lineage, and was well regarded for his intellect. I think it’s important to know that, because I don’t want you thinking of his work as lucky or cavalier. He was brilliant and methodical.

We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely my men we have never heard of… in almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons… who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses.

—Edward Bernays, Propaganda

Drawing inspiration from his uncle's groundbreaking work on the human psyche, Bernays was on a mission to understand subconscious motivations that govern human behavior. I won’t retell his influence in presidential administrations and world wars, but it’s well worth the exploration. Check out this and this.

A watershed moment in Bernays' career was the groundbreaking "Torches of Freedom" campaign. Commissioned by the American Tobacco Company in 1929. This campaign (I’ll admit, one of my favorites) challenged the taboo of women smoking in public. Bernays had arranged for models with hidden cigarettes to walk out in front of the parade at a certain time and place. He had also tipped off the press that something big was happening.

When the stunt unfolded, Bernays guided the media to position smoking as a symbol of women's liberation. This audacious act of defiance, cloaked in the language of empowerment, earned widespread media coverage and quickly changed public perception. He demonstrated such an ability to engineer desire and cultural change that Lucky Strike hired him to figure out how to get women to buy their bright red boxes of smokes. He orchestrated a fashion trend that celebrated green dresses. Spoiler alert: it worked.

When Bernays was picked up as a consultant in the auto industry, it wasn’t enough to inform a populace of some product, especially an expensive one. There’s no money to be made from a person knowing about a car unless they buy a car. More than that, he needed them to be repeat buyers.

Bernays' revolutionary approach was in his use of emotional triggers to promote automobile consumption. It’s the part that gets 21st century social media debates flaring, probably because it’s humbling and a little self deprecating to admit the power of advertising.

Bernays steered car companies away from merely presenting cars as modes of transportation. He positioned them as vehicles of aspiration, promising not just mobility, but a means to a more vibrant and fulfilling lifestyle. Utilitarian considerations were so 19th century. He understood that vehicles could be marketed as symbols of accomplishment and independence. Car companies offered a way for Americans to fulfill cherished ideals.

Bernays also recognized the potency of public gatherings as platforms for influencing consumer perceptions. You call it community engagement, he called it sales. By strategically placing automobiles at prominent events and associating them with the glamor and excitement of these occasions, he magnified their allure. Product placement worked like magic, which is why you still see it today. (Or maybe you don’t notice it because it’s that effective.)

But have you seen the latest model?

“Planned obsolescence” confounds consumers and critics. It’s the business strategy that redefined how vehicles are manufactured and marketed, but has played a pivotal role in fueling consumerism across many industries.

Planned obsolescence is the deliberate design and production of products with a predetermined lifespan. The point is to get customers buying a product more frequently, either because the product (cars in this case) stopped working or looked outdated. Edward Bernays played a key role in this.

The balance of just-good-enough engineering and over-the-top advertising generates artificial demand, pushing consumers towards a perpetual cycle of upgrading. It’s impressive that they’re able to pull this off in plain sight, year after year, decade after decade. Psychologists and marketers understand the allure of novelty and status, and they also understand the average person is clueless to the persuasion.

Culture is downstream from propaganda.

Propaganda will always play visible and invisible roles in shaping culture. For transportation, the influence goes far beyond buying certain types of vehicles.

Americans aren’t car dependent merely because GM and others sell incredible machines that give us the liberty to travel long distances at relatively low costs. At the same time the auto industry was persuading the traveling public to get more and more cars, they were lobbying politicians for infrastructure bills and land use policies that would naturally lead to more car sales.

Housing separated from jobs and other land uses. New highways, wider lanes, bigger intersections, systems designed for speed and minimal delay.

It never ends. If you’re a trillion dollar industry, you do more of what works. Whether it’s the military, pharmaceuticals, or transportation, industries will work tirelessly to shape culture in their favor. When you accept that, life makes so much more sense. Andrew Brietbart famously said “politics is downstream from culture.” I’d add culture is downstream from propaganda.